Why do young musicians bother? Why do they give so much of themselves for little or no return? Why do they stare in the face of utter failure and defeat, running the risk of rejection and humiliation, not to mention death by electrocution? Why do we volunteer on a regular basis for a dose of alcoholic poisoning?

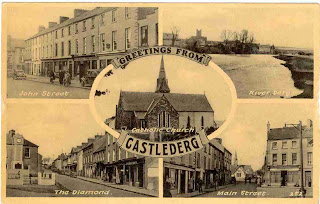

Perhaps the greatest folly of the band’s concert career occurred on Friday 27th February 1981, when we played the Punters Inn in Castlederg, one hundred miles west of Belfast, in County Tyrone, on the border with Donegal. Some gigs are heaven, some gigs are murder, some gigs are not really anything at all, and then there are those gigs that are simply absurd. We drove into the town-square at seven thirty p.m. after a three-hour trek in a hired van. On our arrival in the Punters we were given a very nice sausage supper each, free of charge, along with the promise of a one hundred pounds fee at the end of the night. These were the only two aspects of the whole fiasco that weren’t absurd.

Finally, on Tuesday 10th March 1981, we made it to the Polytechnic at Jordanstown for the last gig of this, our first offensive. It was to be a long one, but a hell of a night to finish on; quite possibly knocking the Pound gig off the ‘best gig so far’ position. A band called Colenso Parade came up from Belfast with us in the van to play support. They were nice people and they sounded good too. The singer, Oscar, sang in a low voice, and the keyboard player was a girl. She was using only a single Yamaha CS-5, the baby brother of my own Yamaha CS-15 synthesiser. Conditions on stage were cramped. In order to get into position behind my Wakemanesque semi-circle of a set-up, we keyboardists had to go into the next room and climb through a conveniently positioned service hatch.

After a long six months since our last performance, we were back on the block. It was, Thursday 24th September 1981, and time again for another Freshers’ Ball in a vomit filled Speakeasy, and a trial run for some new songs. The glorious Sample and Hold were all together more professional, not to mention original, but the Speakeasy crowd responded with studentish indifference. Consequently, this was not a memorable gig.

Well, speaking for myself, I suppose I did it for the glory of it all. There was, after all, a happy possibility that every now and then one might be on the receiving end of a small measure of adoration. For, although publicans have not the slightest respect for bands and their efforts, punters, on the odd occasion when the mood takes them, can be more than appreciative. On these occasions, such as our up-lifting evenings in The Pound and in The Elms, the glory will build like this: The people in the audience have a good time and they show it. The band sees the audience having a good time and feel appreciated. They too have a good time and play well. Consequently, the audience has an even better time and show it more. The band feel even more appreciated, and play even better. The night takes off, and a glorious time is had by all. This is the straightforward ‘glory scenario’, where the glory is facilitated by what we might call The Principle of Reciprocation.

The second source of glory for the more egotistically twisted, such as my-younger-self, sometimes comes in the form of a sort of Inversion of The Principle of Reciprocation. Some performers are gracious, being only too grateful for the indulgence of their public, and happy to receive as a kindness any small scrap of condescending acknowledgement of their efforts. At nineteen years old I wasn’t one of them. In later years, I did get a handle on things, and eventually I did learn how to perform with a degree of humility which held sanity intact, but for the entire lifetime of Sample and Hold, at every performance two things were certain; drunkenness and resentment.

On the sad occasions when The Principle of Reciprocation may become Inverted, such as at our gigs in Spuds, the scenario runs like this: The poor musician in question nearly breaks his back getting the gear up the stairs and setting up, drinking the whole time to dull his pain. The music starts but the audience shows no understanding of, or appreciation for, the band’s efforts. Here, the only glory to be had is a glory akin to that of the battlefield. Joining forces with his fellow musicians on stage, or not (depending on the full extent of his pitiable sense of isolation and alienation), our young musician finds some desperate consolation the only way he can. With the audience in his sights, along with the publican and whoever else he might deem deserving of his wrath, our young anti-hero, abandoning the more subtle sensibilities of his craft, beats the drink down his neck, cranks up the volume, and slices the heads off everyone in his path.

The result may lack subtlety but the energy that is released can be exciting in a way that may even, quite perversely, ‘turn the audience around’. For myself, however, I was invariable too far gone to take any interest in such ironic possibilities of redemption.

|

| egotistically twisted |

On the sad occasions when The Principle of Reciprocation may become Inverted, such as at our gigs in Spuds, the scenario runs like this: The poor musician in question nearly breaks his back getting the gear up the stairs and setting up, drinking the whole time to dull his pain. The music starts but the audience shows no understanding of, or appreciation for, the band’s efforts. Here, the only glory to be had is a glory akin to that of the battlefield. Joining forces with his fellow musicians on stage, or not (depending on the full extent of his pitiable sense of isolation and alienation), our young musician finds some desperate consolation the only way he can. With the audience in his sights, along with the publican and whoever else he might deem deserving of his wrath, our young anti-hero, abandoning the more subtle sensibilities of his craft, beats the drink down his neck, cranks up the volume, and slices the heads off everyone in his path.

The result may lack subtlety but the energy that is released can be exciting in a way that may even, quite perversely, ‘turn the audience around’. For myself, however, I was invariable too far gone to take any interest in such ironic possibilities of redemption.

* * *

Perhaps the greatest folly of the band’s concert career occurred on Friday 27th February 1981, when we played the Punters Inn in Castlederg, one hundred miles west of Belfast, in County Tyrone, on the border with Donegal. Some gigs are heaven, some gigs are murder, some gigs are not really anything at all, and then there are those gigs that are simply absurd. We drove into the town-square at seven thirty p.m. after a three-hour trek in a hired van. On our arrival in the Punters we were given a very nice sausage supper each, free of charge, along with the promise of a one hundred pounds fee at the end of the night. These were the only two aspects of the whole fiasco that weren’t absurd.

The bad news was that the proprietor wanted us to go on at ten forty-five p.m. and play till one thirty a.m. God save us all. We Belfast lads weren’t used to this sort of thing. These were the days before late opening was the norm. Eleven thirty p.m. seemed to us really quite late enough to be out drinking. And indeed it certainly was late enough for those of us with a drinking technique that was designed to put one into a near coma by about eleven.

This was a miserable venue. It represented the antithesis of all that was good and satisfying about our Elms gig. There was no stage. The Punter’s Inn, like the vast majority of music venues, so called, operated a band-stands-in-the-corner-taking-up-as-little-space-as-possible policy. There was a single power point from which to supply the whole band’s gear. However, these technical difficulties paled in comparison to the overriding ‘atmospheric’ difficulties. There were twenty-six people relaxing in the Punters Inn when we got there. That would have been a small but adequate audience to work with; the size of an audience with whom we could have done business, so to speak. But, unfortunately, by the time we had eaten our sausage suppers, got the gear set up, and started to play, all but two of our audience had vacated the premises. It transpired that there was a big new disco joint opening up on another corner of the town-square.

|

| a long way for a sausage |

Castlederg was a strange place. Apparently, as well as its residents being treated to late licenses and big new disco joints, it was not uncommon, the barman told us, for big name bands to perform low-key trial-run debut gigs in this strangely favoured wee town. A few weeks previously, John Lydon’s new band Public Image Limited had played Castlederg, in yet another venue, on yet another corner of that same town-square. And here were we, naively thinking that we were coming to a place where the audience would be nicely starved, and only too grateful for our visit. It served us right, I suppose.

By the end of our first song our remaining audience of two abandoned us in favour of the new attraction. Even then, it wasn’t, as one might have presumed, that the two remaining young ladies had chosen, out of some respect unique among the concert going fraternity, to stay and hear our first number before joining the others at the disco. No, I got the distinct impression that it was simply that their physical constitutions were such that they were unable to get their pints of Guinness down their throats in a period of time any shorter than it took us to play our first tune. This, coupled with a financial constitution that precluded their leaving their drinks behind, as they hurried on to the evening’s ‘real’ entertainment, was, I surmised, the only reason why the young ladies stayed for the few minutes that they did.

In any case, that was the end of the only audience we were to have for the whole night. Any atmosphere out of which the glorious Sample and Hold might have fashioned a night’s entertainment had just been sucked out of the door. The Principle of Reciprocation and even its Inversion was null and void. The situation was hopeless. Pathetically, we struggled to hold up our end of the deal, ourselves and the bar staff in the empty pub. We proceeded to play for a full two and a half hours, and with such a painfully long performance, we had to take all the measures we could to fill in the time. We played all the songs we knew; many of them twice. We even resurrected Gloria, which we hadn’t played since the Devonshire Arms. After Gloria had been noodling along for something like ten minutes, our drummer did a drum solo of all things. I did the odd extended solo myself, and at one point in the proceedings even our guitarist, against his nature, surprised us all with one. A lot of what we tried during this gig-with-no-audience served as experiments in performance possibilities. Sadly, however, just about all of our experiments failed. The one reassuring comfort was that, despite all the cock-ups, our esprit de corps invariably did kick in to save us from going completely belly up on any particular song.

Shortly after one o’clock we called it a night, got ourselves packed up and set off into the cold night for our three hour drive home. The whole thing was a gruelling slog. The one hundred pounds in our pockets did offset the feeling of humiliation a bit, but really it was simple tiredness that dominated the mood in the van. In a way it was all too bizarre to think about. We got back to Belfast and dropped the guitarist off home just in time for him to go straight out the door again to work. I got a lift home from the drummer at six twenty-five a.m., as the sun came up. I made a big fry for the two of us, our sausage suppers of the previous night a distant memory.

|

| intolerably bothersome |

Well knackered and just about rock ‘n’ rolled out, we had two more gigs to go. Tuesday night (3rd March 1981) found us in Winkers. Some Venues are nothing more than a room above a bar, which the owner has opened up with the minimum of investment, in the hope of adding to his coffers by exploiting some unsuspecting young beer swilling musicians and their young beer swilling fans. Winkers was just such a place. It was the first floor of a fairly shady docks pub called The Dunbar Arms, which was the type of establishment that hosted a stripper on Saturday afternoons. As a venue it really was a bit of a non-starter, but it served well enough for those of us keen to get away from the University environs. Awkward narrow stairs made a band’s get-in and get-out intolerably bothersome. As we heaved our monster P.A. up there, we were reduced to something that looked and felt very much like a Laurel and Hardy routine.

Thirteen people showed up for the show, most of whom we knew personally. We weren’t complaining; following the absurdity that was Castlederg, we knew only too well that we could do a lot worse than thirteen. The band was definitely starting to flag, though, and while I myself was miraculously energetic throughout this penultimate gig, this appearance of enthusiasm was deceptive. Given the struggle of getting the cabs and the rest of the stuff up the stairs, not to mention the still smarting Castlederg humiliation, as much as ever before I was running on contempt. The Inversion of The Principle of Reciprocation was in play, and what energy I had was all bad energy.

* * *

Finally, on Tuesday 10th March 1981, we made it to the Polytechnic at Jordanstown for the last gig of this, our first offensive. It was to be a long one, but a hell of a night to finish on; quite possibly knocking the Pound gig off the ‘best gig so far’ position. A band called Colenso Parade came up from Belfast with us in the van to play support. They were nice people and they sounded good too. The singer, Oscar, sang in a low voice, and the keyboard player was a girl. She was using only a single Yamaha CS-5, the baby brother of my own Yamaha CS-15 synthesiser. Conditions on stage were cramped. In order to get into position behind my Wakemanesque semi-circle of a set-up, we keyboardists had to go into the next room and climb through a conveniently positioned service hatch.

I suggested to my colleague that she use my Synth since it was capable of producing all the sounds that the CS-5 could, and it had identical ergonomics. However, as I plugged her CS-5 into a spare channel in my mixer and found a place for it on top of my Vox (looking really cool alongside my CS-15), I realised why my fellow keyboardist had declined my offer. She had the names of the notes written on the keys in felt tip.

The glorious Sample and Hold gave a fine performance despite some complaints from the guitarist’s amp, which was showing signs of fatigue. Just like us, it was suffering mostly from having too much beer poured into it. But apart from the odd technical difficulty, the band was by now a well-oiled and mean machine. Thanks to all our gigging experience the songs were as tight as hell, and we were pretty much unstoppable.

The crowd went mad. A hippie-type young woman came up to the front of the stage and did a snaking-about-sort-of-dance. Our guitarist was doing a bit of snaking about himself and he accidentally hit the hippie-woman on the head with the end of his guitar. It had to happen sooner or later. In fact, it really is surprising how seldom guitarists and bassists hit punters, or fellow musicians. There had been quite a few punters, on other occasions, who actually deserved a good whack on the side of the head. But of all the candidates at all the gigs who might have got thumped on the head with a guitar, this lady was not the one any of us would have selected. Anyway, it wasn’t the end of the world. Love and peace were in the air and, apologies having been given and graciously received, the music and the dancing continued with gusto.

The folks in the Poly didn’t want us to stop. But, we had done all the songs we could to do. So, having worked up to an exuberant and emotional climax, we came off the stage to rapturous applause and a gratifying amount of whooping and whistling. The joint continued to buzz with happiness, excitement and love. So much so, in fact, that we had a word with Colenso Parade, and then, in an unprecedented move, our support band went back on to do a few more songs, and to soak up some of the love. That was the kind of generous band we were; a far cry from the mentality of the scud button.

When Colenso Parade had had enough of their second helpings, the glorious Sample and Hold hit the stage again with a second wind, and well liquored up to boot. We went into overdrive. The crowd flipped. The joint jumped, on stage and off. It was a night of multiple orgasms.

After the show, emotional exhaustion hit us hard. The comedown of loading the van was rough, but a very pleasant woman called Ann Marie came to our rescue. As Entertainments Officer at the Polytech it was she who

had booked us for the gig. By way of showing her appreciation for the night of fine entertainment and love, Ann Marie helped to heave gear about in a very impressive fashion. It was a perfect gesture with which to end a perfect night. We were done in. Never again would we do such a concentrated batch of gigs. Sample and Hold were over-night old hands, experienced rock ‘n’ rollers with the bruises and the rapidly developing psychoses to prove it. Troopers that we were, after only a few days recuperation, we happily resumed our recreational drinking and self-destruction, (as opposed to career drinking and self-destruction). Regardless of all the reasons for not doing what we were doing, the band had been blooded, and we were going to need more gigs. But there was none lined up for, and, for the time being, the guitarist and I returned to our scheming and dreaming. Only, now, we would have some experience upon which to base our extrapolations. Then, as April and May passed, and our second gig-less summer came into view, we began to get moody and artistic all over again. The glorious Sample and Hold was all talk and no action. We annoyed each other with tortured phone conversations about ‘direction’ and ‘band identity’. I bought some tartan trousers, intended as my contribution to ‘stage presence’, which had also become a concern.

|

| stage presence |

* * *

After a long six months since our last performance, we were back on the block. It was, Thursday 24th September 1981, and time again for another Freshers’ Ball in a vomit filled Speakeasy, and a trial run for some new songs. The glorious Sample and Hold were all together more professional, not to mention original, but the Speakeasy crowd responded with studentish indifference. Consequently, this was not a memorable gig.

Nevertheless, in a Proustian sort of way, I myself will never forget a remarkable few moments that occurred during this otherwise unremarkable gig. During ‘Tears of Tolerance’ I lost my concentration. I lost my concentration, big time. This is where things get Proustian. I have a vivid memory of looking out off a first floor window on a late summer’s evening, daydreaming. My thoughts ran like this: “Those people out there crossing the road are students. Some of them are coming into this building, into the Students’ Union. That’s where I am, In the Students’ Union at Queens’.” It was bizarre, like an out of body experience or something. My dislocated thoughts continued, “That’s right, I’m in the Students’ Union. Oh my God, I’m on stage. There are three hundred people looking at me. This music that I’m hearing is being made by me. I can’t think what this song is exactly, but it is definitely the case that I am playing it. Oh Christ, I better not think about it right now. Thankfully, it seems to be sounding all right without me thinking about it. Well, if it ain’t broke don’t fix it.” It was an existential moment, a moment worthy of Sartre’s Nausea.

|

| not really in the room |

All very fascinating it was too, but it was not the sort of parapsychological experiment one wants to be performing while in front of three hundred people, who are assuming, quite naturally, that the people on stage are on the same astral plain as everyone else in the room.

* * *

For the next gig, the glorious Sample and Hold were destined to play to an audience of over a thousand people. It was to be our fist ‘big gig’, and we were to pull it off with only a few hours notice. Thursday 15th October 1981 began like any other Thursday. I sat through my morning classes in the tech. Then, in the middle of a sleepy afternoon lecture, the singer, of all people, appeared at the classroom door. I was intrigued. Our conversation went like this,

SINGER: Whitla hall. Tonight. Right?

ME: Right.

SINGER C’mon.

The gig, a booking secured because the singer was in the right place at the right time, was a support slot for Hazel O’Connor. Operation Big Time was under way. I made my apologies to the lecturer and left my classmates to their note-taking and napping. Rock ‘n’ Roll was calling my name, and I had to go.

A few hours later we arrived at the Whitla and set up our stuff on stage among the main band’s stuff that was already there. Then we hung about back stage while the audience came in. As we peeked out to see the crowd, it was, as expected, massive. The Whitla hall was filled to capacity with around twelve hundred people, scary stuff. We had elephants as well as butterflies in our bellies, and our wee tins of beer were trembling in our sweaty little hands. Still, there was no turning back. This was what we had been working for. Wasn’t it?

We went on at the appointed time and played a set that went like this: 1 Inside, 2 Advert, 3 Blind People, 4 Smile For The Ladies, 5 Drowning, 6 Painful Independence, 7 Never Give An Inch, 8 Whatever Happened To…?. A set of eight original songs, which was more than was on offer from Hazel O’Connor’s outfit.

|

| Whitla |

One of the funnier moments during the show came as the singer leaned over for a word with the guitarist. With some perhaps inappropriate candour, between the lines of whatever song he was singing, he put his hand over his microphone and expressed his heartfelt opinion that the kids who made up the audience were no better than “fucking animals”. the guitarist started to laugh at the sincerity and conviction of the comment. Legend has it that a friend in the audience got a photo of this moment, but I’ve never seen it.

Due to there being two complete band set-ups on the stage at the same time, I ended up perched right up near the front of the stage. There were two young girls below me, practically underneath my keyboard stand. They were no older than thirteen and, to my puzzlement, they kept trying to touch my feet. I was very worried by these apparent gestures of adoration, but later I realised that it was probably more a case of a mocking parody of adoration, not unlike that which was meted out back in the Knock Presbyterian Church hall incident. But it’s best not to dwell on these things.

The Glorious Sample and Hold came off stage to the anticlimax of it all. Hazel O’Connor ran around in a tizzy. “Where’s me skirt? Where’s me skirt?!” she panicked. We stood around with fresh tins of beer in our, now steadier, hands, trying to comprehend that we had just played in front of twelve hundred people, and now it was over. Someone took a photo of the singer with Miss O’Connor just before she stepped onto the stage (with her skirt on).

Then the recrimination started. The singer got on his high horse. The poor bass player got it in the neck. It seemed that his crime was to have interrupted the singer as he was introduction one of the songs. On a whim, the bass player had dedicate the song to a friend in the audience, speaking over the top of the singer’s ‘official’ introduction, in the process. Apparently, this represented an outrageously unprofessional disregard for stage etiquette, an offense akin to that of the ill-judged action back in the Speakeasy, to wit ‘the nudge’. Actually it was all a bit ridiculous, since, really, all that anyone in the audience would have heard would have been one incoherent mumble being augmented by another incoherent mumble. I mean, has anyone ever had the slightest idea what singers are wittering on about between songs?

* * *

The next gig, on 7th November 1981, was another ‘big’ one; a support slot for The Comsat Angels in the Snack Bar, in the Students’ Union. The gig came courtesy of our friend-in-a-high-place, Basil Fox. It wasn’t as prestigious as the Whitla Hall gig but it served the purposes of career advancement.

The Comsat Angels were an English band who would go on to have a long career without ever really making the big time. They were pretty good, I thought. They had a keyboard guy and, among other things, he was using a Hohner Duo, just like the ones used by me and Stevie Wonder. The Comsats guy had an impressively percussive technique on the Duo. Basically he slapped it about, and sort of bunched it a bit. It was a good effect. I made a mental note.

Tim Barnett––he of the incongruous purple tux in The Pound––was at the gig. His hair was red on this occasion. After the gig Tim and a few other regulars said that they thought it was our best performance to date. This was confusing. The guitarist and I were of the opinion that we had played without much feeling. Perversely, perhaps, it seemed to us that the band generally gave a better account of ourselves in front of smaller audiences and on the occasions when it didn’t ‘matter’ so much. Since this gig was a potentially ‘important’ gig, those of us afflicted with a pseudo-Holstian temperament felt unable to give of our best.

Of course the difference of perception between those of on stage and those of us off it, may well have been due to altogether more mundane considerations. For, as ever, the sound on stage had nothing whatever to do with the sound out front.

Three weeks later, on Wednesday 25th November 1981, we found ourselves back in the Polytech for an altogether more heart felt evening. This time we played on our own. While we were never going to match the vigour and expansiveness of the first Poly gig, this was a good solid gig and we worked up a decent enough sweat.