Of all the songs my band practised in our early days during the late seventies, and there must have been more than forty songs all told, only a handful were ever to get a public airing. Musically speaking we didn’t need the hundreds of hours that we spent rehearsing in garages and church halls. But then again, the groundwork in which the band was engaged wasn’t just about music. It had as much to do with learning how to be creative together, in spite of all the grievances and ructions that were to be expected among any group of intense egotistic teenage males. The trick was for us to stay in one room for a reasonable length of time without one of us walking out of it. It’s a small miracle when any band stays together long enough to get to their first gig.

But we made it through this first test, and, on a Saturday afternoon in May 1980, the band attempted a live performance. It was in a Church Hall on the Knock Road in front of a bunch of children and youths. And It was a desperate and pathetic affair. It was all the bass player’s fault. He wrote an outrageous letter to the vicar (or whoever) announcing that our band was in the middle of a “nation-wide tour” and that he thought it would be nice to offer our services to “some of the smaller venues in Belfast” before “continuing on our tour”.

It is quite possible that the vicar invited us along as a kindness, hoping to disabuse us of our fantastical self-delusion. Given the mocking disdain with which the kids treated us, one might even have imagined that they had been privy to our outrageous communication. God only knows, perhaps the vicar may well have pinned the letter to the notice board to give everyone a laugh, or even to illustrate to the young ones in his spiritual care the sad end awaiting those who give way to the temptations of pride and dishonesty.

For the most part, as we presented our music that tragic afternoon, our youthful audience paid us little heed. They didn’t even stop their games of table tennis, and what attention they did pay us we could have done without.

Kids can be cruel and, whatever their reasons may have been, these little monsters went to town on us. They made a laughing stock of us. At one point a group of them paraded around in front of the stage waving a makeshift cardboard banner above their heads in a wounding parody of adoring fans. They had scrawled “George” on their pretend banner because, earlier, when they had asked for the guitarist’s name, to appease them, our singer had told them our guitarist was called George.

|

| Roddy's in front of The Pound |

Earlier in the day said guitarist and I had been in Roddy’s bar. Roddy’s, next door to The Pound, was our regular drinking hole and we’d been there for the whole afternoon. Thus, mercifully, we were pretty well lubricated, and, consequently, de-sensitised to the full horror of the situation. Still, having played a minimal set of just a few songs, we couldn’t get out of that church hall fast enough. It was not an illustrious launch to our concert career. None of us ever spoke of it again, and everything that followed was done in spite of it.

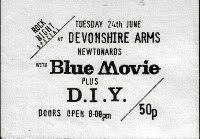

I prefer to think of the embarrassing episode in the Knock Road church hall merely as an ill-advised dress rehearsal. This allowed, we might say that really the band’s debut was a few weeks later on Tuesday 24th June 1980, in the Devonshire Arms in Newtownards, an altogether more happy occasion. We went by the name of D.I.Y., an ad hoc name that we had settled on a few days earlier to facilitate the hurried printing of tickets and posters. ‘D.I.Y.’, perhaps, was meant to evoke the anti-music-industry self-help ethos of punk.

Gary, who had sung with the band for a short while, had, with a little more savvy than the rest of us, organised the gig. We were to play support to Gary’s new band, with the dubious name of Blue Movie. Unfortunately, therefore, the poster that Gary posted outside the Devonshire Arms conjured up all sorts of unsavoury images. It read, “Tonight: Blue Movie plus D.I.Y.”

There was a surprisingly substantial crowd of about eighty souls, which was, I imagine, the best turn out the back bar in the Devonshire had seen in years. As support band, we went on first. We were very nervous behind our moody, nonchalant exterior. But the adrenaline was pumping, and we were more than sufficiently rehearsed. We played a steady gig, and we went down well with the punters. This was the set of covers that we presented:

|

| Connotations |

- I Need To Know—Tom Petty

- Breakdown—Tom Petty

- Bye Bye Love—The Cars

- Furniture Music—Bill Nelson

- Moving In Stereo—The Cars

- Sunday Papers—Joe Jackson

- Dirty Water—Nine Below Zero

- What Goes On—The Velvet Underground

- Ghosts Of Princes In Towers—Rich Kids

Notwithstanding nervousness we had a good time, and D.I.Y. left the stage with the sound of applause ringing in our ears. Gary and his band got up to do their bit, but our excitement was such that none of us heard a note of Blue Movie’s set. As our hosts began to play, we adjourned with breath-taking and oblivious rudeness, to the front bar, where we had some serious drinking and self-congratulation to be getting on with.

The band was just starting to learn the ropes of live performance, and, because of some personal equipment difficulties, I had already learned one important first principle: Creativity and inspiration, skill and proficiency, all come to nought if the technology isn’t capable of delivering the music across to the punters. To coin a phrase: you can’t separate the art from the wires. Often when punters say, “I don’t think much of the band” what they really ought to be saying is, “I don’t think much of the amplification system”. It is not that one needs the best equipment that money can buy. But the gear one relies on must be up to the job. A Hammond C3 might be very nice, but then again, sometimes a Vox Continental is just the thing. The point is your Vox Continental (or whatever) must be in working order.

A second principle, which we all learned at our first gig, was this: The sound that the performers hear while on stage and the sound that the punters hear ‘out front’ are two very different things. As we came off stage, we shared one common observation: “It sounds weird up there”. In all but the best of gig situations, the performers will find themselves listening to a very odd mix of instruments and dislocated noise. Certainly, it is rare, in ordinary amateurish situations, for anyone on stage to hear the singer. Hence the oft seen finger-in-the-ear-folk-type-performance, as singers try to hang on to the tune by listening only to the sound inside their own skulls. There is, therefore, something else that the enlightened punter might take into account when passing judgement on some poor band or other. Not only is it true that a good performance on the part of the band is only part of what makes for a good sounding gig, but unfortunately it is also the case, conversely, that a good sound ‘out front’ doesn’t guarantee a good performance from the band. For it is always possible that, despite a passable sound out front, there may well be an absolutely abysmal sound on stage. Consequently, on occasions when a band sounds good, but seem to be giving less than their best, it may well be because they are the only people in the room who have absolutely no perception that the gig is actually going well.

|

| Ready for a pop star's foot |

After the gig we had considerable difficulty getting out of the town. The Troubles were still at their height and the security gates had been closed for the night. I remember sitting, squashed into the back of someone’s car that was packed to the roof with band gear, drunk and happy enough to not care if we spent all night driving around Newtownards looking for a way out. It had been an auspicious night, and an egotistical time was had by all. Back in Belfast (eventually), celebration and gig post-mortem followed. But really the whole concept of playing music live was lot more complicated than anything the five or us had, as yet, fully to imagine.

The photo had been taken just after the Speakeasy gig. We looked passable, standing and sitting on the concrete back staircase in the Student’s Union. We didn’t look great, but we would do. One real problem with the picture however was that our bass player had his eyes closed. So, before we sent it off to the Chronicle, we salvaged the photo by adding rock star sunglasses with a black felt-tipped pen. The Bass player now looked the best of the lot of us. Which is not to say very much. I myself could not have been less rock and roll if I had tried. I invariably wore ill fitting jeans, (the sort of non-designer-label jeans one buys because they are ‘such good value’) plus a very standard navy jumper, and utterly style-less training shoes (we didn’t say ‘trainers’ back then). My hair was greasy, colourless and longish: by which I mean only that it was not short. It wasn’t any definite length at all, really.

Along with all this I had been wearing the same, infinitely un-hip, Harris Tweed jacket for about a year and a half. Originally, the strategy behind my choice of the Harris Tweed was borrowed from that of the Dadaists and the Surrealists, who had assumed an image of conventionality in order to accentuate their subversive intent. A bit like the bowler hats in Monty Python satire. This was the road I had started down when I was eighteen, but I hadn’t really followed through very well.

Three weeks later (on Friday 14th November 1980) we made our second appearance in the Speakeasy. The gig was heralded in the Belfast Telegraph’s Friday Rock Column, with a short bio of the band and a photo taken around the side of the Students’ Union just before our previous appearance. The gig was a support slot with a band called Male Caucasians, who hailed from the Dunmurry. As I walked in to the Speakeasy and saw the Male Caucasians guys doing their sound check, I was transported in my mind back to a night three and a half years earlier, and the occasion of my first ever gig … picture goes all wobbly … cascading harp music…

* * *

There was another gig the following Tuesday (1st July 1980). We returned to the Devonshire Arms to play second fiddle again to Blue Movie, this time under our new mane of Sample and Hold. In the days leading up to the gig the bass player warned against counting our chickens before they were hatched. As it turned out, he had a point. To our dismay, only about seven punters showed up for the show this time. It seemed that the gratifyingly large audience of the previous week was not something we had any right to expect.

Naturally, our egos were bruised, but we did take some consolation from the fact that the ‘crowd’, while reduced, was enthusiastic. They even demanded an encore, and we obliged by shambling our way through Gloria. As we started into it I assumed an air of sophisticated condescension. I sought to portray myself and my colleagues on stage as new generation rockers, paying a merely tongue in check homage to the rockers of the past. My affected little smirk was saying “Oh all right then, we’ll do Gloria just to show that we can do that old stuff if we want to, but don’t imagine we 1980s guys take any of this outmoded stuff seriously or anything, I mean it’s not like we think Gloria is an ‘important’ song or anything”.

|

| That's Jim with the glasses in front of Van |

In actual fact Gloria (originally recorded by Them in 1967) was a extremely important song, with near mystical significance for me. At the end of my schooldays just a few years earlier, I had spent nearly every Saturday afternoon grooving in The Pound Music Club. Local hero, and former member of Them, Jim Armstrong wowed the Pound regulars with his mastery of the electric guitar. Armstrong had a series of bands in the seventies within which to showcase his talents. The band I remember best was called Light. Appropriately enough a twelve-minute guitar-saturated version of Gloria had been adopted as the show-stopping climax of Light’s Saturday afternoon sets. We lapped it up. Punters would be hanging from the rafters chanting along, “Gloria. G-L-O-R-I-A, Gloria”, and screaming for more. It was an adolescent ritual of quasi-religious proportions.

Admonished by the poor turnout at our second and last Devonshire Arms appearance, the band retreated to lick our wounds. There were no gigs to be had in Belfast in the summertime, so we practised a few new songs, dropped a few old songs, had a few drinks, made some plans and dreamed some dreams. We also wrote a song of our own.

The summer came to an end and, on Friday 3rd October 1980, we played at the Freshers’ Ball in the Speakeasy: one of the venues in Student’s Union building at Queen’s University. This was the first of many gigs we were to do around campus. Along with it we got our first mention in newsprint. The Students’ Union Gown newspaper read as follows:

The first big booze-up of the year will be, of course, the Freshers’ ball on Friday October 3rd. The kicking, punching, scratching and biting starts when the doors open at 8.00 p.m. ... introducing the bands––THE RUBBERS, RICHMOND HILL and SAMPLE & HOLD (that was not a misprint, that is their real name).

It was disappointing that this young journalist felt it necessary to draw attention to our name in such a negative way. Surely it wasn’t that difficult to grasp. Just for the record then, “Sample and Hold” had two senses. First, it could be taken as an invitation to one and all to come and try out our music. And then, having heard us, those who felt so inclined were further invited to embrace us and to retain our services. Fairly literally then, the invitation was to sample us, and to hold us. Second, for those with a passing acquaintance with electronics jargon, “Sample and Hold”, was meant to indicate quite simply that we were a band that was a bit more keyboards orientated than were some of our peers.

Along with the free publicity we also got sixty pounds for our trouble, this being our first pay cheque. I don’t think any of us had really thought about getting paid for playing music until this moment.

The crowd was made up of some five or six hundred of the new crop of students, just out of school. The Freshers’ Ball was an essential part of the rites of passage for the keen ones. Back in 1980 I was something of an inverted snob and I had a dislike of students; sour grapes really. I just envied students their extended childhood, as they gently entered adulthood, protected in their cushioning cloisters from the abrasions of a working life.

Upon my carbuncle of envy there now grew a wart of contempt. The Speakeasy crowd, to my eyes, displayed stereotypical student-type apathy, and my jaundice view of their fraternity was substantiated. It seemed to me that not knowing the misery of a full week’s work there was no urgency in their attempts at escapism. While I applauded their, undoubtedly sincere, drinking efforts, I found them to be sadly inexperienced and inept, and very disturbing to look at. There was vomit everywhere.

Notwithstanding my personal politics of envy, the students in the Speakeasy on this particular Friday night stepped outside of their stereotype. Despite their affected apathy, there was a perceptible reaction to our sound. They could not help but prick up their ears as we hit the stage to give our newly penned original song its first nervous airing. Heads turned at the freshness of our synthesiser-driven music. Heads turned, even among the throng scrambling for their lager and their vodka at the jammed-up trough that was the Speakeasy bar. Sample and Hold were on the stage and heads turned.

* * *

Gig number three was to be in Spuds in Portstewart (Monday 19th October 1980), and, in the hope of getting some publicity for it, we sent off a letter and a photograph to The Coleraine Chronicle. They printed the photo along with this write-up: “Sample & Hold,” a band who produce “1980’s pop music,” are making a debut appearance in Spuds, Portstewart, this Friday night October 24. The five cite Bill Nelson, XTC, Lou Reed, Roxy Music and several other new wave/reggae bands as influences on their music. ...” It’s funny to think that it seemed okay and even sophisticated for us to credit ourselves with making “1980’s pop music”. With hindsight it’s hard to think of very much in the history of music that is less sophisticated than 1980’s pop music.

|

| Subversion in Disguise |

Of us all the bass player, perhaps, had at least some claim to an active policy on image. He said that he was ‘anti-image’. By fastidiously avoiding any item of attire that might have been perceived as fashionable, or that may have attract attention of any kind, he sought to guard himself, I suppose, against the accusation of being a poser. ‘Poser’ was a damning and much bandied term of abuse in the early eighties. Unfortunately, however, there was no escape. For, if our bass player was serious about his non-image being intentional (unlike my own), then, as a would-be pop star with an every-day appearance, it was clear that he was merely posing as a non-poser. Life can be difficult when you’re young, not to mention paradoxical.

When we got to Spuds (Friday 24th October 1980 ) we discovered that there had never really been any chance of the proper turnout, for which, naturally, we had hoped. Friday night, it transpired, was simply not the right night to be playing Spuds. Saturday night was the ‘happening night’ up there, and the only good reason for a band to play on a Friday night, was to ‘get in’ with the management and maybe, thereby, to ‘earn’ a gig some other time, on a Saturday. Sample and Hold never did get in with Spuds’ management, and we never did earn a Saturday slot.

Nevertheless, while we played to only the most modest of crowds, all was not lost. There was a young punter in attendance who, single-handedly, made it worth the trip. He really enjoyed himself, as he danced all by himself to our impressively faithful rendition of Bill Nelson’s Furniture Music and a few other numbers besides. The glorious Sample and Hold had their first glorious fan. After the gig our fan thanked us and complemented us on our inspired choice of music. He may have been a mere schoolboy, but this guy was on the ball. He had more of an idea about Sample and Hold’s image and musical direction than we had ourselves. This was the sort of feedback we needed.

I never caught his name but clearly this fan of ours was sincerely delighted with the idea of a band in Northern Ireland playing electronic sounding pop music. I think he was, at heart, in the vanguard of New Romanticism, God love him. In return, I thanked him for his enthusiastic, if rather strange, dancing.

The sixty miles to Portstewart on the North Coast was a bit of a trek for us Belfast boys. So, for our Spuds gig we hired a van from a guy called Billy Maxwell. Billy's Ford Transit was probably not actually roadworthy, but it came cheap and since Billy was doing the driving this meant that, as we hit the M2, everyone could relax, by which I mean that those who were so inclined could drink heavily.

|

| A Transit from that era |

We needed a van, now. We had a lot of gear. Since we were intent on bashing the music out pretty much as loud as we could, our singer needed something more than a spare guitar amp to give his tonsils a bit of a leg up. To this end we had resolved to keep our hire-costs low by building up a nice big P.A. system all our own. At this point, just three gigs into our concert career, we were surprisingly well on our way towards our dream of a one thousand watt system, or, as we technicians like to say, ‘a 1K rig’. We had four one-by-fifteen bass bins, a pair of two-by-twelve mid range cabs and a pair of high frequency horns for up on top. We also had an impressive looking twelve channel mixing desk. To power all this we had a couple of one hundred watt slave amps, and for the time being we still had to hire a main power amp.

The good thing about having our own P.A. was that we soon became familiar with how all the cabs and stuff might fit together to make the journey to and from gigs as comfortable as possible, especially for the poor suckers who got jammed in the back. A method developed whereby the guitarist would stand in the van and stack the gear as logic dictated while the rest of us handed him the drum cases, amps, cabs and boxes, as required. I say ‘the rest us’, but I myself did a lot more than my fair share of the work. From the outset we two took pride in our work. Nothing ever got damaged. Nothing ever rattled about or came adrift as the van bumped along home. Best of all, we who were consigned to ‘the back’ could travel in style. We had comfortable seats, made from bass cabs and coats and cushions, with mid range cabs and drum cases to lean back on. With just a few more gigs for practice, there would no longer be a race for the front seat in the van. If it was a sleep you were after on the way home, the place to be was in the back with the gear.

* * *

As we continued to learn the ropes of live performance, I realised another important principle of rock ‘n’ roll regardinging a balancing act with chemicals affecting the brain. On the one hand there was the adrenaline, which was out in force due to excitement and occasional nervousness. On the other hand there was the antidote: alcohol. The procedure for maintaining an equilibrium was delicate and had at least three stages:

Stage one: Getting drunk enough to go on stage, with a few tins in the van on the way to the gig, and then a few pints from the bar while we got the gear set up.

Stage two: Getting drunker and drunker while on stage. This meant having a relay of friends and associates planted in the audience, who would be kind enough to bring up the drink at very regular intervals as we worked our way through the set.

Stage three: The inevitable crash. The moment we hit the last note of the last song, the tension and excitement was spent and the adrenaline was gone. The equilibrium was dashed. A nosedive into utter crapulence ensued.

|

| The band in 1980 |

It was in the spring of 1977. I got my first sniff of stardom in the Wilmer, a celebrated hard rock venue favoured by bikers and other longhaired types, in the seaside town of Newcastle at the foot of the Mourn Mountains. The main act for the night was Emerald, a straight-ahead rock band doing Thin Lizzy covers. A couple of years down the road Emerald would change their name to Male Caucasians.

|

| Brubeck: early role model |

I performed as half of a duo with a guy called Mark, who was another graduate from the ‘Dunmurry school of rock’. Dunmurry on the southern outskirts of Belfast was a hotbed of musicians and would-be popsters. I had teamed up with Mark just a few weeks earlier having answered his ad in one of the music shops. It wasn’t a support slot as such for mark and me, but more a matter of us doing a few numbers while the ‘big boys’ in the ‘real band’ took their break. Nevertheless, I was only sixteen and, as I remember it, it was quite an impressive début. We played four tunes in all. On the last song, one of Mark’s, I played electric guitar and I even did a solo. The first two songs in our mini-set were also Mark’s creations, but the third number was a five minute unaccompanied solo for me on my Crumar electric piano. The piece I played was a jazzy thing inspired by Dave Brubeck: not at all usual fare for the Wilmer. I was scared to bits, naturally, but I kept my head down, concentrated on the music, and gave a pretty good account of myself. I had been developing my unnamed little piano extravaganza since I was twelve or maybe even younger. Getting to play it live was a dream come true.

When I finished my brave little virtuoso performance on that heady summer evening, it took a few moments for me to come back down to earth. When I did, I realised that just about everyone in the capacity audience of scary bikers and backdated hippies was applauding. Some were even a-whoopin’ and a-hollerin’. It also dawned on me at that moment that the place had been respectfully quiet while I had been playing. I was a hit. About fifteen years of ego-related problems were to follow.

No comments:

Post a Comment